What is Cognitive Load Theory?

And how can it improve the way you learn?

Cognitive load theory explains how we process information. It tells us that too much data (or data with too much complexity) reduces memory and learning. This article discusses how we can manage cognitive load in our lessons and gives five principles to reduce cognitive load for our students.

As teachers, cognitive load theory is a fundamental principle that should inform our teaching decisions, as it can critically affect our students’ learning outcomes.

Where is cognitive load theory from?

Sometimes abbreviated to CLT (not to be confused with ‘Communicative Language Teaching’), cognitive load theory came from research into problem-solving by John Sweller in the 1980s.

Sweller built on previous research that showed that working memory has a limited capacity and described the relationship between working and long-term memory.

This diagram shows the rough process of processing and remembering information:

As you receive information, the senses pass some of it onto your working memory, while some is ignored (you can’t take in every detail in your field of vision!).

Your working memory might rehearse the information for clarity (or not), and then it’s processed (or encoded) into your long-term memory. The same is true in reverse when you recall information you want to use.

Your working memory acts like a gatekeeper, as it works hard to filter all the information it receives and decides which to keep.

Unfortunately, working memory isn’t that large (some people have said it’s like the RAM on a computer, whereas long-term memory is like a hard drive). So working memory can suddenly become a bottleneck when it hits its processing limit.

When our students are learning in our lessons, there are several ways that we can overload their working memory. Let’s look at the different ways this can happen.

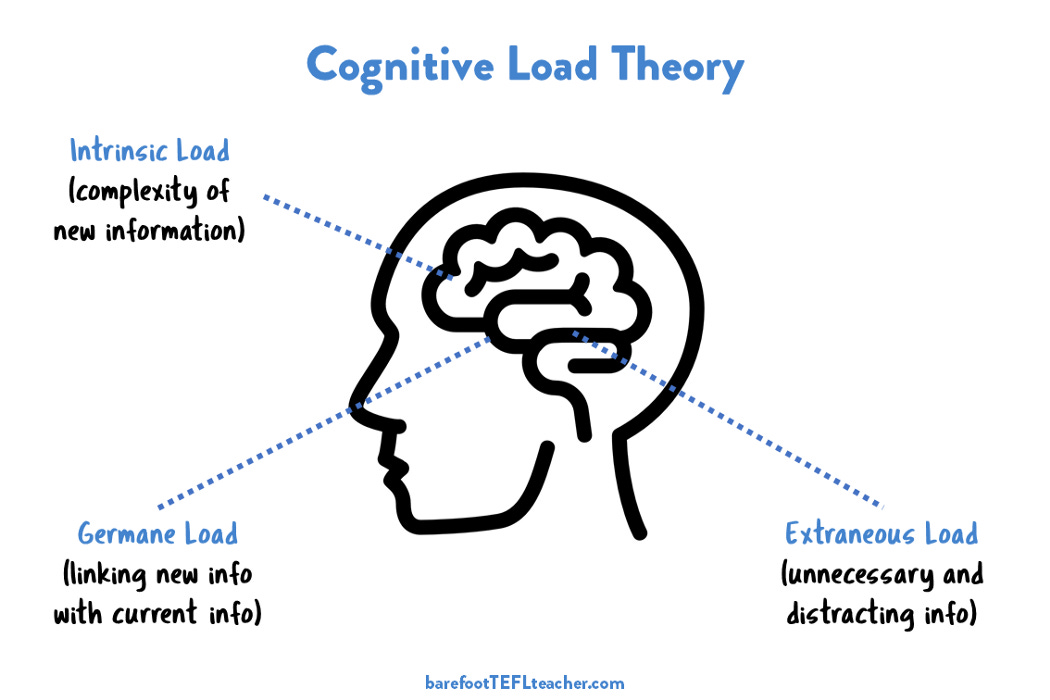

Types of cognitive load

Sweller noted that cognitive load types fall into three broad classes.

1. Intrinsic cognitive load

Intrinsic cognitive load is how complicated the topic or task is. Calculus is innately more complex than simple addition, and most would agree that the present simple is more accessible to grasp than the third conditional. The intrinsic load is higher in these tasks because the complexity is higher.

2. Extraneous cognitive load

Think of extraneous cognitive load as extra information that distracts from the critical information you want to get across. Too much information, too confusing, or unnecessary information.

We see this in the classroom as overly complex or poorly designed materials or a noisy environment (or even overly complex teacher instructions).

3. Germane cognitive load

Germane cognitive load looks at how easy it is for students to link their current knowledge to additional information. It’s part of the processing as the brain encodes the information into long-term memory.

5 principles to reduce cognitive load

Richard E. Meyer developed these in a 2002 paper. Remember them when you’re planning your lessons and in the classroom!

1. The coherence principle

Reduce the amount of information to only what’s necessary. Keep things simple, and focus on clarity over style.

This typically applies to two critical areas in a class:

Materials (where possible!). Don’t write unnecessary instructions. Make sure images are unambiguous.

Teacher Talk (e.g. giving instructions). Grade your language to their level. Don’t overload students with too much information when you speak. Leave room to think when you ask them a question.

Top tip: differentiation is a key strategy in managing intrinsic cognitive load in the classroom.

2. The signalling principle

Highlight important information somehow. Draw attention to it. Applies to both spoken and written information.

Top tip: when you speak, alter your pacing. Pause dramatically. Whatever you do, don’t speak in a monotone at all times.

3. The redundancy principle

A classic example of this is reading the information from a screen.

While it might be necessary to present information in different formats for your students, do it because they might need it, not because of lazy teaching.

Top tip: don’t keep repeating instructions when students already ‘get it’. Same for language points that they’ve already mastered.

4. Spatial contiguity

Show things related to each other, close together (or at least show that they’re linked).

For materials, if you’re labelling a diagram, don’t add the label three pages after the image. Make sure related items are close together.

Top tip: Use common sense to closely link items and their meanings!

5. Temporal contiguity

The same as (4), but with time instead of space. So, link related concepts together without leaving significant gaps. You wouldn’t suddenly jump to a topic from 10 minutes ago without warning in conversation and expect students to understand!

Top tip: when presenting language to learners, it’s better to present linked items (I.e. an image of an item and the name of that item) together as soon as possible.

For both temporal and spatial aspects, it helps to present language in context. This is fantastic for helping with germane cognitive load, as it automatically links the information to a relatable situation.

Final tip

Don’t make things too simple!

I’ve seen teachers go to extremes and make things so simple that it affects clarity. Materials that are too simple become hard to understand because they’re ambiguous. Overly simplified spoken language can become grammatically incorrect or be a flawed language model.

The key is moderation.

General CTA

If you liked this article, you’ll love my books:

📝 Lesson Planning for Language Teachers - Plan better, faster, and stress-free (4.5⭐, 175 ratings).

👩🎓 Essential Classroom Management - Develop calm students and a classroom full of learning (4.5⭐, 33 ratings).

🏰 Storytelling for Language Teachers - Use the power of storytelling to transform your lessons (4.5⭐, 11 ratings).

🤖 ChatGPT for Language Teachers - AI prompts and techniques for language teachers (4.5⭐, 10 ratings).

💭 Reflective Teaching Practice Journal - Improve your teaching in five minutes daily (4.5⭐, 16 ratings).