PPP vs ESA: When to Use Each

And why most teachers are taught this incorrectly.

I spent years feeling guilty about using PPP.

My CELTA trainer made it sound like a relic from the 1960s. “It’s teacher-centred,” she said. “The research doesn’t support it.” I nodded along, scribbled notes, and then walked into my classroom in China the next day and used it anyway.

Because it worked. My students improved. The lesson flowed. I wasn’t scrambling.

So why did I feel like I was doing something wrong?

Here’s what I wish someone had told me back then: You do not need to abandon PPP or force ESA into every lesson. You need to know what problem you’re solving.

Most teaching frameworks fail not because they’re outdated, but because we use them to solve the wrong problem.

Let me explain.

The real difference between PPP and ESA

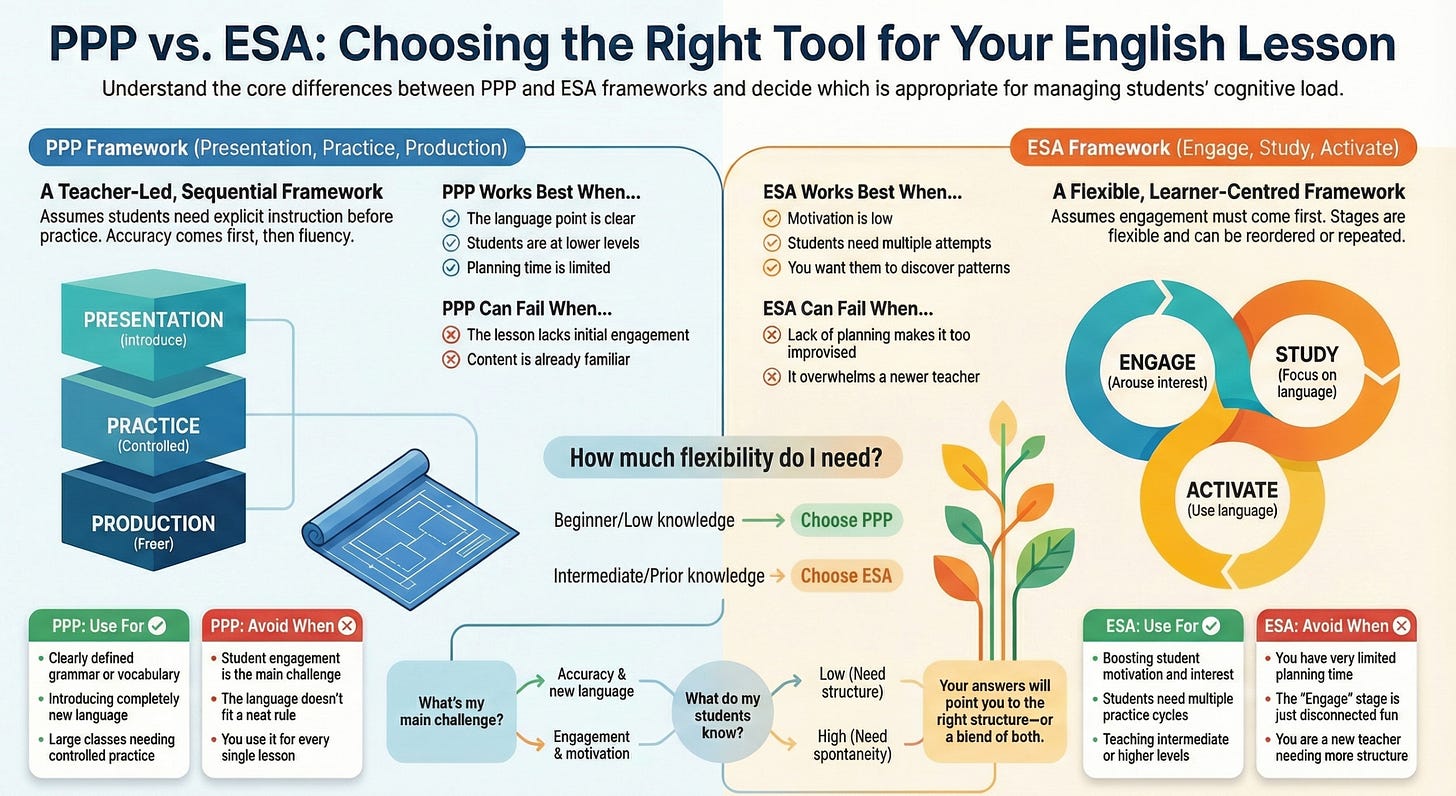

On the surface, PPP (Presentation, Practice, Production) and ESA (Engage, Study, Activate) look almost identical. Three stages. Language input. Controlled practice. Freer output.

So why the fuss?

The difference isn’t in the stages themselves. It’s in the assumptions behind them.

PPP assumes: Students need explicit instruction before practice. The teacher controls what language gets introduced and when. Accuracy comes first, then fluency.

ESA assumes: Engagement must come before instruction. The stages can be rearranged. Students might need to cycle back through stages multiple times in a single lesson.

Neither assumption is wrong. But each fits different situations.

When PPP works brilliantly

PPP shines when:

You’re teaching a clearly defined grammar point or lexical set. Second conditional? Modal verbs for advice? PPP handles these cleanly.

Your students need explicit instruction. Lower levels especially benefit from having the language presented, clarified, and practised before they’re asked to produce it freely.

You’re short on planning time. PPP is logical and sequential. Most coursebooks follow this structure. You can plan a solid PPP lesson in fifteen minutes if you know the pattern.

You have large classes where monitoring is tricky. The controlled practice stage lets you check everyone’s accuracy before opening things up.

Your students expect a traditional structure. Some learners feel lost without clear teacher guidance. PPP provides that.

I’ve taught hundreds of PPP lessons. When the language point is clear and the practice is well-scaffolded, students genuinely improve. That’s not theory. That’s observation.

When PPP falls apart

PPP struggles when:

Students are bored. If you launch straight into presenting grammar without context or engagement, you’ve lost them before you’ve started. Their minds wander. Minor misbehaviour creeps in. You’re fighting an uphill battle.

The language doesn’t fit a neat pattern. Functional language, chunks, discourse markers - these don’t always slot into a tidy presentation-then-practice model.

Students already half-know the material. If you present something they’ve seen before, they’ll tune out during the presentation. Then they’ll coast through practice without really thinking.

You use it every single lesson. Any framework becomes tedious when repeated endlessly. Higher-level students especially will start to disengage.

The critics aren’t entirely wrong. PPP can become mechanical. But that’s a misuse problem, not a framework problem.

When ESA works brilliantly

ESA shines when:

Engagement is the real challenge. Tired students? Monday morning? Teenage class that would rather be anywhere else? Start with Engage. Get them interested first. Study comes easier once they care.

You need flexibility. ESA’s stages are like Lego bricks - you can arrange them in different sequences. Straight arrow (E-S-A), boomerang (E-A-S-A), patchwork (E-A-S-A-S-E). You respond to what’s happening in the room rather than marching through a fixed plan.

Students need multiple attempts. The boomerang sequence lets students try an activity, focus on form, then try again with improved accuracy. This is particularly effective when you can see they’re close but making consistent errors.

You want students to discover language patterns themselves. Instead of presenting rules, you can engage, then have students study examples and work out patterns inductively.

ESA is fundamentally about responsiveness. If you’re comfortable reading a room and adjusting on the fly, ESA gives you permission to do that.

When ESA falls apart

ESA struggles when:

Teachers treat it as a loose structure that doesn’t require planning. Flexibility isn’t the same as improvisation. A patchwork lesson still needs to be designed intentionally.

The “Engage” stage becomes entertainment for its own sake. Showing a funny video is not engagement if it doesn’t connect to the lesson. Students need to see why this matters to them.

Teachers add stages without purpose. More isn’t better. Adding E-A-S-A-S-A-E doesn’t make a lesson more effective - it often just makes it confusing.

The flexibility overwhelms newer teachers. If you’re still working on classroom management and timing, ESA’s flexibility can feel like too many decisions to make at once.

ESA requires confidence. You need to trust your ability to read the room and make good choices in the moment.

The secret that explains both: cognitive load

Here’s what I wish my CELTA trainer had mentioned: cognitive load theory explains why both frameworks succeed or fail.

Cognitive load is simple. Your students’ working memory has limits. Overwhelm it with too much information, unclear instructions, or distracting materials, and learning grinds to a halt. Students look busy. They’re not learning.

PPP works because it breaks learning into stages. Present a manageable chunk. Let students practice it with support. Then let them produce it more freely. Each stage reduces the cognitive demand compared to asking students to do everything at once.

ESA works because engagement primes the brain for learning. When students care about a topic, they’re willing to invest mental effort. The flexible staging lets you add support exactly when students need it.

Both fail when teachers ignore cognitive load:

Too much new vocabulary in one lesson

Instructions that take three minutes to explain

Activities that require students to listen, read, speak, and remember grammar rules simultaneously

Jumping between topics without clear transitions

The framework isn’t the problem. The amount of stuff you’re cramming into students’ heads is the problem.

Simple signals that tell you which structure to use

Stop worrying about which framework is theoretically superior. Instead, look at your students and your lesson aim, then ask these questions:

Choose PPP when:

The language point is clearly defined

Students haven’t encountered this language before

You need to maximise controlled practice time

Your planning time is limited

Students expect and respond well to explicit instruction

Choose ESA when:

Motivation or engagement is your main challenge

Students need multiple cycles of practice and feedback

The language is better discovered than presented

You want flexibility to respond to what happens in class

Students are intermediate or higher and need less scaffolding

Or blend them. Add an engaging context before your PPP presentation. Use the ESA boomerang structure but with a clear PPP-style study phase. These aren’t religions. They’re tools.

A quick decision checklist

Before your next lesson, run through this:

What’s my main aim? (New language? Fluency practice? Review?)

What do my students already know? (Nothing? Something? Quite a lot?)

What’s my main challenge? (Engagement? Accuracy? Time?)

How much flexibility do I need? (Fixed plan? Room to adjust?)

Your answers will point you toward the right structure - or the right blend of structures.

The real lesson here

I wasted too much mental energy worrying about whether I was using the “right” framework. That energy would have been better spent thinking about my students.

What do they need to learn? How can I break it down so they’re not overwhelmed? How can I make it interesting enough that they want to engage?

Answer those questions well, and PPP will work. ESA will work. TTT will work. Task-based learning will work.

Get those wrong, and no framework will save you.

So stop feeling guilty about PPP. Stop forcing ESA where it doesn’t fit. Use the structure that solves the problem in front of you.

That’s what good teachers do.

What’s your go-to lesson structure? Hit reply and let me know - I read every email.

Until next time,

David

P.S. If you want to dig deeper into lesson structures, cognitive load, and practical planning techniques, my book Lesson Planning for Language Teachers covers all of this in more detail. It’s written for busy teachers who want evidence-based techniques without the academic waffle.

If you liked this article, you’ll love my books:

📝 Lesson Planning for Language Teachers - Plan better, faster, and stress-free.

👩🎓 Essential Classroom Management - Develop calm students and a classroom full of learning.

🏰 Storytelling for Language Teachers - Use the power of storytelling to transform your lessons.

🤖 ChatGPT for Language Teacher 2025 - A collection of AI prompts and techniques to work better, faster.

💭 Reflective Teaching Practice Journal - Improve your teaching in five minutes daily.

You're quite right that those questions should be driving planning, rather than the lesson structure you want to go for. I wonder how many teachers really think in those terms, anyway, and like the methodology that underpins the planning move towards a principled eclectic approach.

Also very curious to hear about your CELTA tutor's comments about PPP. I did mine in 2011 and certainly didn't hear any such criticisms (quite the opposite, in fact)!