How to teach with task-based language teaching (TBLT)

A step-by-step guide to using TBLT in the classroom.

I remember the first time I saw task-based learning in action. I was observing a colleague’s class, expecting the usual routine - present some grammar, drill it, then maybe a role-play at the end. Instead, she walked in, set up a scenario, and told the students to plan a surprise party with a tight budget. Then she stepped back.

For the next twenty minutes, students argued, negotiated, compromised, and laughed. They were using English because they had to, not because the teacher told them to. When one student said “we should buying the cake from Tesco,” nobody stopped to correct her. The communication kept flowing.

I was hooked. But I also had no idea how to recreate it in my own classroom.

If you’ve heard about task-based language teaching (TBLT) but aren’t sure how to actually do it, this article is for you. I’ll walk you through what it is, why it works, and how to plan your first TBLT lesson - step by step.

What is task-based language teaching?

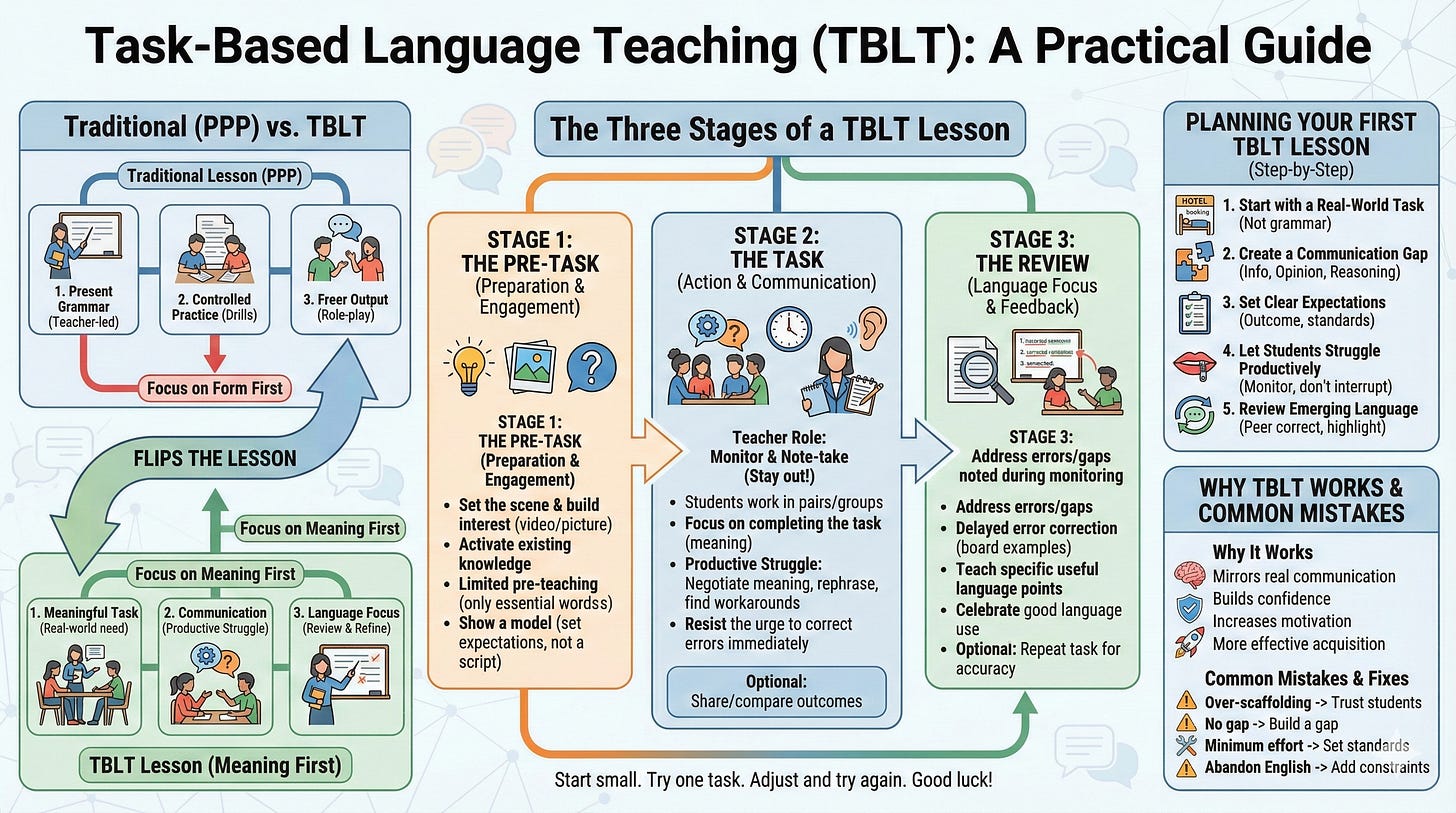

Also called task-based learning, TBLT flips the traditional lesson on its head.

In a typical lesson, you might teach a grammar point, get students to practice it in controlled exercises, then finally let them use it in a freer activity. The grammar comes first, and the communication comes later.

TBLT reverses this. Students start with a meaningful task - something they’d actually need to do in real life - and use whatever language they can to complete it. The teacher’s job is to set up the task, support students while they work, and help them notice and improve their language afterwards.

The key word here is “meaningful.” A task isn’t just any activity. It has a clear goal, it requires students to communicate to achieve that goal, and there’s some kind of outcome at the end. Planning a trip, solving a problem, comparing options, reaching a decision - these are tasks. Filling in blanks or repeating dialogues? Not so much.

Why bother with TBLT?

You might be thinking: this sounds like a lot of effort. Why not just stick with what works?

Fair question. Here’s why I think TBLT is worth your time.

It mirrors real communication. When you use a language in the real world, you don’t think “now I’ll use the present perfect” before speaking. You focus on meaning, and the grammar comes along for the ride. TBLT replicates this. Students learn to communicate first and refine their accuracy second.

It builds confidence. Many students freeze when they have to speak because they’re terrified of making mistakes. In a TBLT lesson, the focus is on completing the task, not on being perfect. This takes the pressure off and helps students realise they can actually communicate, even with limited language.

It increases motivation. Let’s be honest - grammar drills are boring. Tasks are engaging. When students are genuinely trying to solve a problem or make a decision, they’re invested. And invested students learn faster.

It works. Research consistently shows that TBLT leads to better communication skills and deeper language acquisition than traditional methods. Students don’t just learn about the language - they learn to use it.

The three stages of a TBLT lesson

Every TBLT lesson follows roughly the same structure. Think of it as three phases: before, during, and after the task.

Stage 1: The pre-task

This is where you set the scene and get students ready. You’ll introduce the topic, build interest, and make sure everyone understands what they need to do.

You might show a picture or video to spark curiosity. You might activate their existing knowledge by asking what they already know about the topic. You might pre-teach a few essential words - but be careful here. The goal isn’t to front-load all the language they’ll need. It’s just to remove any barriers that would prevent them from attempting the task.

If your task is complex, this is also where you’d show a model or example. Not a script to follow, but enough to set expectations for what a successful outcome looks like.

Stage 2: The task

Now comes the heart of the lesson. Students work in pairs or small groups to complete the task.

Your job during this phase? Stay out of the way.

This is harder than it sounds. Every instinct will tell you to jump in and correct errors, offer vocabulary, or guide struggling students. Resist the urge. Your role is to monitor - listen, observe, take notes - but let students work through the challenge themselves.

The struggle is productive. When students have to negotiate meaning, rephrase ideas, and find workarounds for language they don’t have, that’s when the real learning happens.

Once groups finish, you might have them share their outcomes with the class. Did different groups reach different conclusions? Did anyone approach the task in an unexpected way? This comparison stage adds another layer of communication and keeps everyone accountable.

Stage 3: The review

After the task, it’s time to focus on language.

This is where you address the errors and gaps you noticed during monitoring. Maybe several students struggled with the same structure. Maybe someone used a creative but incorrect phrase that’s worth discussing. Maybe you heard some great language that deserves praise.

You can do this through delayed error correction, where you write examples on the board and ask students to identify and fix problems. Or you might teach a specific language point that would have helped them during the task. The key is that this language focus comes after the communication, not before.

You can also ask students to repeat the task - or a similar one - now that they’ve had some language input. Often, you’ll see a noticeable improvement in accuracy the second time around. It’s quite satisfying to watch.

Step by step: planning your first TBLT lesson

Ready to try it yourself? Here’s how to plan a TBLT lesson from scratch.

Step 1: Start with a task, not a grammar point

This is the biggest mindset shift. Instead of asking “how can I teach the past simple?”, ask “what real-world task would naturally involve the past simple?”

Think about what your students might actually need to do with English. Book a hotel. Compare job candidates. Plan an event. Solve a customer complaint. Choose a holiday destination.

Start there, and let the language follow.

Step 2: Make sure there’s a gap

A good task requires students to communicate because they have information, opinions, or reasoning that others don’t have.

There are three types of gaps you can build into a task:

Information gap: Students have different pieces of information and must share them to complete the task. For example, Student A has the train times, and Student B has the prices.

Opinion gap: Students have different preferences or viewpoints and must discuss them to reach a decision. For example, choosing the best candidate for a job when each student values different qualities.

Reasoning gap: Students must work out how to get from A to B, solving a problem or making a plan. For example, organising a day trip with constraints on time, budget, and transport.

Without a gap, there’s no real need to communicate - and students will take shortcuts. I’ve learned this one the hard way.

Step 3: Set clear expectations

Before you let students loose, make sure they know what success looks like.

What’s the outcome? A decision? A plan? A presentation? A written proposal? Be specific.

If you think students might do the bare minimum, set standards. “You need to consider at least four options.” “Everyone must contribute at least two ideas.” “Your final plan should include times, costs, and responsibilities.”

For weaker or younger learners, showing a model can help - but be careful not to turn it into a template they copy.

Step 4: Let students struggle productively

During the task, bite your tongue.

I know it’s painful to hear mistakes and not correct them. But interrupting breaks the flow of communication and shifts the focus from meaning to form. Students stop trying to express their ideas and start trying to please you.

Instead, circulate and listen. Jot down interesting errors, good language, and communication breakdowns. You’ll use these in the review stage.

If a group is completely stuck, you can offer a hint or prompt - but try questions first. “What are you trying to say?” or “Is there another way to express that?” often gets students unstuck without you handing them the answer.

Step 5: Review the language that emerged

After the task, bring the class back together. This is your chance to teach.

Put some of the errors you heard on the board. Can students spot what’s wrong? Can they correct each other? This peer correction builds awareness and keeps students engaged.

You can also highlight language that would have been useful. “I noticed some of you wanted to say X but didn’t have the words. Here’s how you could express that.” This kind of just-in-time teaching is more memorable than front-loading vocabulary before students have felt the need for it.

And don’t forget to celebrate the good stuff. When a student used a phrase particularly well, share it. A bit of positive reinforcement goes a long way.

Common mistakes and how to avoid them

TBLT sounds simple enough, but there are a few traps that catch teachers out. I’ve fallen into most of them at some point.

Mistake 1: Over-scaffolding until it becomes PPP

If you pre-teach all the vocabulary, provide sentence frames, and guide students heavily during the task, you’ve essentially turned it back into a traditional lesson. The whole point of TBLT is that students have to figure things out for themselves. Too much support removes the productive struggle.

Fix: Only pre-teach vocabulary that’s absolutely essential. Trust your students to cope with a bit of ambiguity. They’re more resourceful than you might think.

Mistake 2: Tasks that don’t require communication

If students can complete the task without talking to each other, it’s not really a TBLT task. Working individually on a worksheet, even a creative one, doesn’t count.

Fix: Build in a gap. Make sure students genuinely need each other’s input to succeed.

Mistake 3: Students do the minimum

Without clear expectations, some students will take shortcuts. They’ll agree immediately without discussion, use their first language, or let one person do all the work.

Fix: Set clear standards upfront. Require a certain number of contributions, a certain level of detail, or a presentation at the end that everyone must participate in.

Mistake 4: Students get overexcited and abandon English

Sometimes a task is so engaging that students forget they’re supposed to be practicing English. They switch to their first language, shout over each other, and complete the task in two minutes flat.

Fix: This is actually a sign you chose a good topic - they’re invested! Next time, add constraints that force more deliberate communication. Require written notes, slow them down with more complex criteria, or stipulate that everyone must agree before moving on.

Quick task ideas to try tomorrow

Need some inspiration? Here are a few adaptable tasks you can use with different levels and topics. Feel free to tweak them to suit your students.

Survival scenario: Your plane crashes on a desert island. You can only save five items from the wreckage. Agree on which items and why. (Works with vocabulary for objects, modals for necessity, persuasive language.)

Job interview panel: Each student plays a hiring manager with different priorities. Review three candidates and agree on who to hire. (Works with describing people, comparing, justifying opinions.)

Event planning: Plan a class party with a limited budget. Decide on food, activities, and decorations. (Works with suggestions, prices, preferences.)

Mystery solving: Give different students different clues about a crime or mystery. They must share information and work out what happened. (Works with past tenses, deduction, questioning.)

Product pitch: Groups design a new product and pitch it to the class. The class votes on the best one. (Works with descriptions, persuasion, presentation skills.)

Final thoughts

Task-based learning isn’t magic, and it probably won’t work perfectly the first time you try it. Your task might be too easy or too hard. Students might finish in five minutes or need twice as long as you planned. The language review might feel a bit awkward.

That’s completely okay. Like any teaching approach, TBLT gets easier with practice. Each lesson teaches you something about your students, your tasks, and your own instincts as a teacher.

The reward is worth the effort though. When you see students genuinely communicating - arguing, laughing, problem-solving - you’ll understand why so many teachers never go back to the old way.

Start small. Try one task this week. See what happens. Then adjust and try again.

Good luck - and have fun with it.

If you liked this article, you’ll love my books:

📝 Lesson Planning for Language Teachers - Plan better, faster, and stress-free.

👩🎓 Essential Classroom Management - Develop calm students and a classroom full of learning.

🏰 Storytelling for Language Teachers - Use the power of storytelling to transform your lessons.

🤖 ChatGPT for Language Teacher 2025 - A collection of AI prompts and techniques to work better, faster.

💭 Reflective Teaching Practice Journal - Improve your teaching in five minutes daily.

Great explanation and examples. I’ve been looking for a simple description with clear stages and lesson examples and this it! Thanks.

Beautiful explanation and illustration! Thanks!